|

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||

The fossil fuel revolution was a fundamental breakthrough in human history. It was as significant for our species as the transition to agriculture. Coal contains much higher levels of energy per given weight than equivalent amounts of renewable biomass (wood). Exploiting coal on a large scale, humans were able to burst through the ceiling on economic growth that had been in place since the modern human species appeared about 200,000 years ago. At the start of Big Era Seven, world coal output per year was less than 10 million metric tons. Then things began to change, thanks mainly to steam-powered pump engines, which allowed coal miners to drain the water that tended to accumulate in mine shafts and tunnels. By 1860, the world produced about 130 million tons of coal. In 1900, production rose to an astonishing 1 billion tons, and coal provided 90 percent of total world energy consumption. Many more people. A second major source of environmental change was population growth. In 1700, world population, according to one estimate, was about 603.4 million. By 1913, it had nearly tripled to about 1.79 billion. The environmental impact of this dramatic population increase, combined with the surges in economic growth and energy consumption, was colossal. Let us consider some major factors. At first, the population increase was disproportionately concentrated in western Europe, where numbers increased from 81.4 million in 1700 to 261 million in 1913, despite the emigration of millions of Europeans to overseas states and colonies. Later in the era, the populations of Asia and Latin America also increased dramatically. For example, Asia’s population (excluding Japan) grew from 374.8 million in 1700 to 925.9 million in 1913, an increase of nearly two and a half times. World Population Trends in Millions1

In some isolated regions, notably Siberia, Australia, many Pacific islands, and some areas of tropical rainforest, indigenous populations declined. This was mainly because outsiders introduced infectious diseases to which the inhabitants had weak immunities. Epidemics were sometimes locally catastrophic, comparable to the Great Dying in the Americas relative to population size. In the late eighteenth century, for example, a pestilence on the Siberian peninsula of Kamchatka carried off as many as 75 percent of the local inhabitants. When European settlers started arriving in New Zealand in 1840, the indigenous Maori population may have numbered 100,000 or more. By 1858, it declined to 56,000, owing mainly to diseases that Europeans brought with them. Rapid urbanization accompanied world population growth. In 1800, only nine cities in the world had a population of 1 million or more. By 1900, twenty-seven cities had more than 1 million people. The proportion of the world’s people who lived in cities, rather than in rural areas, increased from 2 percent in 1800 to 10 percent in 1900. Mass migrations. Steamships and railroads made major migrations of peoples possible in Big Era Seven. More than 50 million people emigrated from Europe (including Russia) during the era, two-thirds of them permanently. Most of them were looking for work, opportunity, and the prospect of higher living standards than they had enjoyed in their native lands. Their destinations were mainly the world’s temperate zones: Canada, the United States, Algeria, and Siberia in the Northern Hemisphere; Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand in the Southern Hemisphere. Indigenous peoples resisted these newcomers, but in many places they were eventually demographically swamped by them. For example, the population of the territory that now constitutes the United States may have been as high as 10 million in 1500, and those people were all American Indians. According to the 2000 census, by contrast, the population classified as American Indian or Native Alaskan numbered just over 2 million, a number representing only about 0.7 percent of the total population of 281.4 million. These overseas migrations of Europeans also had a significant environmental impact. This is because Europeans and their descendants possessed both sophisticated machine technology and expectations of relatively high standards of living. Therefore, they tended to exploit natural resources more intensively than did the peoples they replaced.

Another pattern of migration continued from the previous Big Era. Between 1750 and 1870, about 1.7 million Africans were moved involuntarily to the Americas, most of them destined to work on sugar and coffee plantations in Brazil or the Caribbean. After 1800, however, the proportion of people of African descent living in the Americas declined relative to the number of people of European ancestry. This happened because so many more Europeans migrated to the Americas in the nineteenth century than did before 1800. Also, the average life span of African slaves was significantly lower than that of European immigrants to the Americas. A third pattern was the migration of Asian laborers. Between 1830 and 1913, some 30 to 40 million Indians and about 15 million Chinese left their countries to seek work in mines and on plantations in European colonies and Latin American countries, as well as in Southeast Asia, the Pacific islands, and South Africa. In the earlier decades of the century, many Asians migrated under contracts of indenture, which offered them free or cheap transport in return for a specified number of years of employment. Many of indentured migrants were treated unfairly and left worse off than they had been at home. Many Asians migrated to the U.S., Canada, and Australia to build railroads. Many became permanent settlers, though others eventually returned home. By one estimate, more than 100 million people world-wide were involved in long-distance migrations during Big Era Seven. Finally, we must also mention the millions more who migrated within the lands of their birth to seek work and opportunity in cities or other regions of economic growth. Internal migrations were an important aspect of change in India, China, Russia, the Ottoman Empire, Africa, and Latin America. Environmental impact of industrialization and migration. The Industrial Revolution transformed the ability of humans to reshape the world’s environment. Deforestation increased on a global scale. So too did water pollution from chemical and agricultural discharges into lakes and streams, and atmospheric pollution from the burning of huge amounts of coal. The advent of railroads and steamships also hastened the diffusion of plants and animals to new parts of the world. This was an extension of the Columbian Exchange of biota that occurred in the previous Big Era. The spread of new plants, such as maize, wheat, and cassava into areas where they had previously been unknown, underwrote large population increases. But environmentally adverse consequences also occurred. For example, in 1859 a farmer in Australia introduced a few rabbits for hunting. Within a few years rabbits were hopping across the continent by the millions, ravaging crops as they went. By 1950, Australia’s rabbit population numbered 500 million and continued to wreak havoc on agriculture.

Despite the global economic advances of Big Era Seven, several major famines occurred. In fact, famines intensified as a result of increased global economic integration, which sometimes devastated peasant societies and sharpened social inequalities. In 1846-49, for example, a series of regional blights ruined potato harvests in Ireland and Eastern Europe. The resulting food deficit provoked many deaths and mass migrations. Even more distressing were the famines of 1876-1902, which historians have linked to climatic conditions produced by the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), a cyclical warming of sea surface temperatures combined with changes in sea level pressure in the southern Pacific basin. Although grain was available to feed the hungry, colonial economic policies justified its continued export to industrial countries for profit. Millions died in parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, and countless millions more were reduced to poverty. Some historians believe that the late nineteenth century famines, coming when they did, were instrumental in producing the gap in living standards that subsequently divided the developed from the underdeveloped world.

|

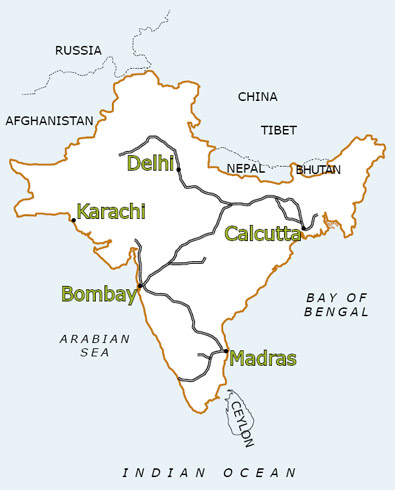

India’s railway network as of 1872. India, a British colony, had a larger rail system in the later nineteenth century than any other Asian country. Map adapted from Daniel R. Headrick, The Tentacles of Progress: Technology Transfer in the Age of Imperialism, 1850-1940 (New York: Oxford UP, 1988), 67 |

|

|---|

When necessary, however, European powers were willing to gain economic advantages using strategies that contradicted the free market. In the previous big era, Asians had been mostly unwilling to import European goods because they did not want or need them. This had been a key economic weakness for European manufacturers and merchants. As a result of the Opium War (1839-1842), however, Britain used naval force to compel the Chinese government to open its market to opium grown in India, then a British colony. This traffic enabled Britain to balance its trade with China for the first time in history. Following the war, the British government imposed a series of treaties on China that gave Britain favored and unequal trading privileges. British merchants regarded this course of events as a case of practical liberal reform, but it led to a large flow of silver out of China to pay for opium, which weakened the already strained Chinese economy. It also led to debilitating opium addictions for millions of Chinese.

The British iron steamship HMS Nemesis (far right) destroying Chinese war junks in the Opium War, 1841. “Destroying Chinese War Junks,” painting by E. Duncan, 1843, National Maritime Museum, London Wikimedia Commons |

|

|---|

In the second half of the era, European and American governments followed suit, establishing, by armed intervention, privileged enclaves in Southeast Asia and China. In 1854, Japan also had to sign an unequal treaty with the United States and then with major European powers. These unequal treaties were the norm not only for European trade with Asia but also with Latin America and the Middle East. States wishing to trade with Britain had to set low tariffs on British imports and adopt legal and other measures favorable to British interests. In the course of the nineteenth century, other European countries, as well as the United States, imposed similarly unfavorable commercial treaties on many countries.

Following the discovery of gold in California in 1849 and later discoveries in Australia, Alaska, and South Africa, a new cycle of global economic growth set in. The increased availability of this precious metal led in 1878 to the establishment of the gold standard, which fixed the value of all currencies in terms of gold. For the first time, there was a single global financial market, which liberals regarded as a progressive reform. For others, the gold standard set up terms of trade that led to the impoverishment of their countries.

Between 1880 and 1914, the world economy underwent a second major wave of expansion. Global growth increased threefold, world trade fourfold, and international investment eightfold. The modern communications revolution, including the building of railroads in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, the global expansion of steamship travel, the laying of the trans-oceanic telegraph cables, and the invention of the telephone, greatly enhanced the movement of peoples, goods, and capital worldwide. The mechanization of agriculture in both Europe and temperate regions where Europeans settled made it possible to produce, process, and transport food more cheaply and efficiently. The steel and chemical industries emerged as a new focus of production and profit just when innovations in the textile industry were slowing down.

The era also saw major economic consolidation. In accord with liberal principles that valued accumulation of private capital and the sanctity of property, new cartels and trusts were formed whose wealth dwarfed any business organizations previously known in history. Two examples were U.S. Steel and Unilever Brothers. The dark side of wealth accumulation was that increased integration of the world market made economies more vulnerable to financial crashes that could wipe out vast sums in a moment.

Political trends. Big Era Seven began with the rise of Britain as the leading global power, overshadowing France and all other countries. The Seven Years’ War and the American Revolution bankrupted France and stripped it of nearly all its possessions in Canada and India. But despite Britain’s great power, it still had to accommodate itself to the consequences of the revolutions that occurred in the Thirteen Colonies of North America, France, Haiti, and the Latin American colonies of Spain between 1774 and 1830.

The revolution in the British Thirteen Colonies of North America was the first of the Atlantic revolutions. The others were the French Revolution (1789-99), the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), and several revolutionary movements in Latin America (1810-28). In both the United States and Latin America, revolutions involved the founding of republics dominated by affluent middle classes. Voting was at first confined to property-holding adult males, and slavery was left largely undisturbed. Nevertheless, the visible contrast between the huge profits made by plantation owners and the misery of laboring slaves provided an engine for political change. The anti-slavery movement was an important part of liberal reform in the Americas in the first half of Big Era Seven. The success of the revolution on the French-ruled island of Saint Domingue in 1804 ended slavery there and produced the Republic of Haiti, the world’s first state governed by descendants of enslaved African immigrants.

Prior to 1789, kingship provided the dominant political model ever since the origins of civilization. Following the French Revolution, individuals would no longer be subjects of monarchs who ruled by “divine right.” Instead they became citizens possessing specific rights and duties embodied in a system of laws, to be enacted by legislatures composed of the people’s elected representatives. This represented a major change in human political organization. Between 1789 and 1914, many monarchies were replaced by republics throughout the world, though the degree of democratic participation in these republics varied widely. Or, as in the British example, monarchs were made subordinate to parliaments and other democratic institutions. Henceforth, kings had to respond to pressure from liberal-minded elites to incorporate democratic political features, such as constitutions and elected assemblies.

Another major political transformation was the abolition of slavery. As a result of decades of anti-slavery protests, the British and American governments abolished the slave trade in 1807 and slavery as a legal institution in Britain’s colonies in 1833. The defeat of slavery, however, was incomplete. For one thing, other European states, like Spain, France, and Portugal, failed to follow the British example immediately. Also slavery continued in the United States until its abolition in 1865, after a bitter and protracted civil war. Brazil and Cuba did not abolish slavery until the late 1880s. Serfdom, a different form of unfree labor, was abolished in Russia in 1861. This said, it is important to recognize that slavery was replaced by other forms of coerced labor, such as indentured labor.

Overall, liberal political and economic ideas provoked great opposition and struggle. While some elites, notably merchants, manufacturers, government bureaucrats, educators, and some church leaders endeavored to implement the liberal reform package of rights and representation, other groups steadfastly resisted these reforms. Opposition came especially from commercial planters, established landowners, military officers, and some religious authorities. In societies as diverse as Mexico, Brazil, Egypt, Turkey, China, and Japan, attempts to implement a liberal reform package divided elites and caused prolonged social struggles. From a global perspective, the civil war, abolition, and reconstruction in the United States fit into this pattern of conflict between liberal and anti-liberal forces.

Colonial encounters. The modern revolution deepened the extremes of wealth and poverty in the world, and the expansion of European colonial empires greatly widened this gap. Colonial rule assumed many forms and produced contradictory results. In South Asia, Britain spent much of the era incorporating numerous pre-existing territories and kingdoms into a unified Indian colonial empire. In Africa and mainland Southeast Asia, the chronology was different. Before the 1870s, European territorial expansion in Africa was largely confined to Algeria and South Africa. In Southeast Asia, the Dutch ruled part, though not nearly all, of Indonesia. From the 1870s to 1914, however, most of Africa, with the exceptions of Ethiopia and Liberia, came under some form of European colonial rule. In Southeast Asia, Britain expanded in Burma, France in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, and the Netherlands in more remote parts of Indonesia. European expectations of new wealth and markets impelled much of this expansion.

The Battle of Adowa in Ethiopia, 1896. A well-armed Ethiopian force under the command of King Menelik II defeated an Italian army. Ethiopia was the only African country to defend itself successfully against European invasion in the late nineteenth century. Artist unknown Photo by Ross Dunn |

|

|---|

In all these places local populations resisted European takeover, sometimes mustering large military forces, sometimes fighting in guerrilla bands, sometimes striving for religious or political reforms that might keep invaders at bay. However, European forces equipped with up-to-date weapons, including portable artillery and the Maxim gun, an early form of machine gun, put down almost all organized resistance. Once they set up their colonial governments, they proceeded with systematic extraction of raw materials from their colonies, including rubber, cacao, peanuts, tropical oils, and minerals. In 1800, Europeans controlled some 35 percent of the earth’s land area. By 1914, they dominated about 88 percent.

Humans and Ideas

In Big Era Seven the ideas of the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment sank deep roots in Europe and spread widely to other parts of the world, especially within elite culture and city-dwelling middle classes. On the other hand, peasants and workers who could not read and write tended to be unacquainted with these ideas, at least until later periods.

Charles Darwin, 1809-1882. United Kingdom postage stamp Photo by Ross Dunn |

|

|---|

The rise of secularism. For Liberals, human progress was obviously desirable and inevitable, and science challenged earlier understandings of nature and the universe. Many educated people in Europe saw experimental science as a rival of religion as a system of thought. Opponents of reform, however, deplored the dizzying change and the weakening of religious and moral traditions. In fact, the modern revolution set off a major cultural struggle between advocates of science and defenders of traditional religions. Scientific explanations of the universe assumed that things happened without intention or purpose and that the universe was inanimate, rather than a manifestation of supernatural power. Scientific perspectives on the earth’s geology challenged the Biblical story of the Great Flood, while Charles Darwin’s book The Origin of Species (1859) provided a new perspective on the place of humans in the scheme of nature. Gradually a secular, that is, “worldly” or non-sacred, culture emerged that accepted the premises of modern science and challenged the cultural dominance of religious organizations and doctrines.

This “secularization” was an important part of the modern revolution, first spreading through Europe, then throughout the rest of the world. Advocates and opponents of secularization struggled mightily over many issues, including the role of religious institutions in education, the rights and privileges of religious denominations, and the place of women in public life. Liberal-minded secularists believed that science and technology would inevitably banish superstition and backwardness. Christian, Muslim, Jewish, and other believers argued that scientific explanations dismissed God, undermined moral standards, and left humans without spiritual guidance or direction.

Most leaders of secular culture also believed that progress was a uniquely European idea generously made available to the world. Many even used Darwin’s theory of evolution to demonstrate the racial and moral superiority of Europeans over other peoples on the grounds that Europeans were making more material progress than others and were therefore the “fittest” members of the human species.

Nineteenth-century racism. This distortion of Darwinism became a justification for racism and colonial rule. Suspicion and disdain among social and cultural groups, who regarded one another as strange and inferior, had been common in world history for millennia. What emerged in Europe, however, was a supposedly scientific racism that cloaked theories of European racial superiority in the vocabulary and methods of modern biology and anthropology. This “pseudo-science” provided a moral justification for both colonial conquest and the systems of inequality that governed colonial societies. Popular race theories had in fact no sound basis in science, but this seemed of no consequence to those who wished to justify imperial rule and economic exploitation of colonial labor and resources.

Thriving religions. The advance of secular culture challenged the world’s religions, but, even so, most of the major faiths grew at a faster pace than ever. The printing of religious scriptures and other theological and spiritual writings, as well as their global dissemination, tended to make beliefs and practices within the leading religions more uniform. Propelled by the new communications technologies, Christian missionaries of various denominations spread their faith to Africa, Asia, and the Americas, where communities frequently adapted its teachings and rituals to local social and cultural ways. The spread of European settler colonies also greatly facilitated the diffusion of Christianity in the temperate regions. Islam and Buddhism took advantage of railroad and steamship technology to expand into new regions, partly in connection with the migrations of Asian and African workers. Pilgrims traveled in larger numbers than ever to holy sites—Roman Catholics to Rome, Muslims to Mecca, Hindus to the banks of the Ganges—where they identified intellectually and emotionally with a larger community of co-believers.

Opposition to rapid change, liberal practices, and European colonialism often took religious form. Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, and Confucian leaders protested foreign rule and growing social inequalities in their lands. Numerous sects arose to preach millenarianism, a word related to “millennium” and referring to a “thousand years” of justice on earth. Millenarian ideology centered on the idea that supernatural forces would bring about a sudden change to end foreign domination, social inequality, and even all evil. Millenarian movements included the Ghost Dance religion of American Indians on the Great Plains, the Tai’ping Rebellion in China, and the appearance of the Mahdi in the Muslim Sudan, an individual divinely inspired to establish a “reign of peace.” Ultimately, none of these movements withstood the power of modern weaponry.

Liberal, democratic, and nationalist ideas around the world. Outside Europe, debates over reform and progress pursued complex paths. In countries as diverse as Turkey, Russia, Mexico, and China the supporters of economic reforms stressed the benefits of liberal economic improvement. However, because these reforms tended to make economic inequalities worse, they had little popular appeal, leading to counter-movements in support of those impoverished by change. Also, traditional elites such as landowners, church officials, and high-ranking military officers saw these changes as undermining their way of life and therefore resolved to resist them.

The ideology of the Atlantic revolutions had profound influence on political reform movements. In many ways struggles over these ideas continue to this day. At the beginning of the era, slavery was broadly accepted and widely practiced. By 1914, the notion that humans could be conceived as property was broadly condemned, and slavery itself legally abolished throughout much of the world. The fact that industrialists and commercial farmers continued to substitute other forms of coerced labor for slavery, and that the struggle against slavery continues today, does not detract from this achievement.

At the start of the era, the holders of power almost everywhere in the world viewed the notion of popular sovereignty, that is, that people are citizens, not subjects, and should have the right to vote and hold office, as dangerous nonsense. By 1914, the principle that the right to govern belongs to the people and not to a divinely appointed monarch, was deeply engrained in the industrialized countries. The struggle for the enfranchisement of women also got underway, though it made much greater gains in the early twentieth century.

Karl Marx, 1818-1883 Author of The Communist Manifesto. Wikimedia Commons Public domain |

|

|---|

A third transforming idea was that workers have rights, among them the right to organize to advance their economic and social interests. In Big Era Seven, workers’ rights gradually gained momentum in industrialized countries. A major stimulus to worker organization was the thought of Karl Marx, whose Communist Manifesto (1848) presented an alternative vision of history centered on the interests of the working class. Marx’s writings, together with those of other socialist authors, had their roots in the ideas of the European Enlightenment and the Atlantic revolutions, but they also offered a critique of liberal reform and its failure to address inequality.

Finally, there was nationalism, one of the greatest forces contributing to the modern revolution. Although we see the world today as self-evidently divided into nations, this was not always so. In 1750, monarchy was the prevailing form of government, while language and ethnicity, though important, were not viewed as the proper basis on which to organize states. Individuals were subjects and not citizens. By 1914, things had changed dramatically. Most people in Europe and the Americas widely accepted the nationalist principle that a “people” defined by shared language, culture, and history had a natural right to govern themselves. Nationalism sought to convince individuals to merge their hopes and dreams with those of the “imagined community” of the nation, that is a community that had distinctive cultural characteristics in common but whose members did not for the most part know one another. The rise of nationalist thought was linked to growing literacy and public education. It was also connected to the mechanization of printing, the growth of a market for printed works, and the diffusion of newspapers and other print materials by way of the new communication technologies. Generally, the leaders of states encouraged nationalism, proclaiming that the interests of the state and the nation were one. Nationalism was therefore a potential antidote to social divisions within a society: wealthy capitalists, middle classes, and the laboring poor should subordinate their economic differences and conflicts to common loyalty to the nation-state. In the later nineteenth century nationalist ideas became an important factor in politics in such places as the Ottoman empire, the Austrian empire, Egypt, China, India, and South Africa.

The modern revolution involved not only economic and political changes but a profound cultural upheaval. It reshaped our understandings of the natural world and the place of humans in it, our basic economic and political understandings, and our sense of cultural identity. Today, we are conscious that the modern world is radically different from all earlier eras.

Teaching Units for Big Era Seven

Definition of Panorama Teaching Units

7.0 |

The Modern Revolution |

PowerPoint Overview Presentation: |

Complete Teaching Unit Download Options:

|

Definition of Landscape Teaching Units

7.1 |

The Industrial Revolution as a World Event, 1750-1850 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

7.2 |

The Atlantic Revolutions as a World Event, 1750-1830 |

||

7.3 |

People, Power, and Ideology: A whole new world, 1830-1900 |

Complete Teaching Unit |

|

7.4 |

Humans in a Hurry: Nineteenth century migrations, 1830-1914 |

||

7.5 |

The Experience of Colonialism, 1850-1914 |

||

7.6 |

New Identities: Nationalism and Religion, 1850-1914 |

Definition of Closeup Teaching Units

6.6.1 |

Leaders of the Enlightenment |

||

7.1.20 |

Living Rooms |

||

7.5.1 |

Resistance to Imperialism in Africa, Asia, and the Americas |

Footnotes:

1 Angus Maddison, World Economy: A Millennial Perspective (Paris: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2001), 241.

Note:

Documents in Portable Document Format (PDF) require Adobe Acrobat Reader 5.0 or higher to view, download Adobe Acrobat Reader.

Documents in Powerpoint format (PPT) require Microsoft Viewer, download powerpoint.

Documents in OpenOffice format (ODT) require Oracle OpenOffice, download Oracle OpenOffice.

Documents in Word format (DOC) require Microsoft Viewer, download word.

|

World History for Us All is a project of the UCLA Department of History's

Public History Initiative, National Center for History in the Schools. Project Support | Conditions of Use |